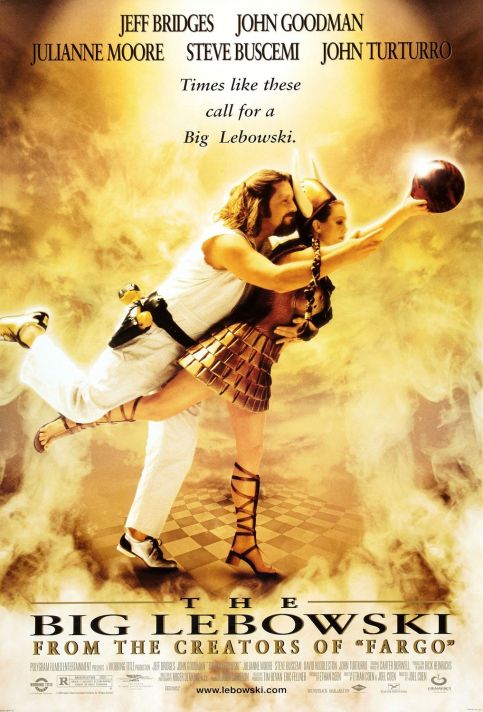

Hall of Greats: The Big Lebowski

What is The Big Lebowski?

It’s a film about bowling and being carefree. It’s about White Russians and rugs. It’s about gangsters and misunderstandings. And so very much more. It’s also the film I have watched more than any other film, ever. I’ve seen it dozens of times and I practically have it memorized. But it’s so well-executed, timed so perfectly, and filled with such genius that it never gets old.

Concisely summarizing the labyrinthine plot of The Big Lebowski and still doing it justice is extremely difficult. The tone of the film is immediately set with a Narrator (Sam Elliot) speaking about a man. It’s not long before Narrator starts rambling and loses his train of thought, and we’re brought into a grocery store where this man Narrator is talking about, Lebowski (although he goes by The Dude), is writing a check for 69 cents to purchase some half & half. The Dude (Jeff Bridges) spends his days and nights at the local bowling alley with his best friend, unstable Vietnam war veteran Walter (John Goodman) and idiotic sad-sack tag-along Donny (Steve Buscemi). These men exist for bowling. Returning home one night, the Dude is attacked by a pair of men demanding to know where their money is. They commit what is apparently the cardinal sin in the Dude’s eyes: they urinate on his rug.

According to the Dude, “this aggression will not stand” (he had just seen President Bush’s speech on the television earlier). It turns out that the gangsters had the wrong Lebowski: there’s another Lebowski, a millionaire businessman/philanthropist, whose wife owes money to the gangsters. The Dude makes a trip to the Big Lebowski’s mansion to request a replacement rug. After enduring a long tour from Lebowski’s horribly spineless and neurotic assistant (a delightful Philip Seymour Hoffman), the Dude is denied his rug from the cold Lebowski, who labels the Dude a “bum” and kicks him out. Of course, the Dude takes a rug anyway; his old rug “really tied the room together”.

What follows is a remarkable and impossibly elaborate series of events, spiraling downward into a fever dream of a misadventure. The Dude has his rug reclaimed by Lebowski’s estranged daughter Maude (Julianne Moore, exceptionally strange here), who makes paintings of vaginas. Lebowski’s wife is kidnapped and held for ransom by some German thugs, but not everyone is convinced. The Dude’s car gets stolen and apparently a young schoolkid & son of a famous television writer is the culprit. Millionaire adult entertainment moguls get involved. So much happens over the course of the film that it is impossible to detail completely.

Jeff Bridges is a marvel as the Dude. This is a role that feels as though it was tailor-made for him; he is the Dude. While the Dude is such a lazy, useless human being, there’s an endlessly endearing quality to him; he’s lovable in spite of being a a pot head, a slacker, and a complete idiot. He’s barely self-sufficient, yet even though his talents don’t extend past bowling and making White Russians, he’s lovable. Similarly, John Goodman is perfect as Walter. Walter is John Goodman’s favorite of his roles, and it is easy to see why. Walter is a time bomb of tension, frequently exploding into anger and even pulling his gun over something as trivial as a bowling game. Yet, his hypervigilance from his time in Vietnam, his overeagerness to help out with the kidnapping situation (and subsequent botching of the case at every single step), and his aggressive Jewish faith make him a joy to watch. Everyone else is great, too. Philip Seymour is such a spineless butler it practically inspires hatred. Julianne Moore in particular is completely out of her element as the completely bizarre art-obsessed feminist intellectual. One of the highlights is John Turturro as a strange and creepy bowler who calls himself “Jesus”, sans the Spanish pronunciation. As with all Coen films, the entire cast has fantastic chemistry and it always appears as though they are having a blast.

Dialogue has always been an extremely, almost unfairly high-quality element of Coen Bros. films. From the hyper-exaggerated Southern speak of Raising Arizona to the gently satirical script of Fargo, the Coens consistently deliver incredibly good dialogue. There’s not a great deal of emotional depth to the script of The Big Lebowski, but the humorous lines are delivered at a breakneck pace and is about the closest a straight comedy has ever come to being pretty much all killer and no filler. While the story is rather inconsequential in the grander scheme, and that doesn’t really seem to be any reason for anything in the film, every line is carefully and meticulously laid out in true Coen fashion. Many of the conversations the trio has are utterly pointless in the way that only three middle-aged slackers could make them, but they make sense. It all works to the creation of the characters or the advancement of the plot. And in a movie where the main character says “man” over 130 times, that’s worth some credit.

Roger Deakins, long-time cinematographer for the Coens, once again does his job marvelously here, along with director Joel Coen. Their visual style is distinct and pleasing. There is an air of meticulous handiwork in the visual style of the film, from the occasional peripheral oddity in the background of a shot, to the set design (the Dude’s apartment is a bizarre collection of things that one might find at a yard sale), to the elaborate dream sequences that are essentially a patchwork of visual imagery assembled from prior smaller cues from earlier (actually, the dreams are literally only composed of things that appeared earlier in the film, albeit much more artistically in the dream). While the film is grounded in reality, there’s something ever-so-slightly off-kilter about it, as though it forgot it was no longer the 70s and still needs to catch up. On top of that, the diverse licensed soundtrack headed by Bob Dylan’s “The Man in Me” is treat to listen to alongside viewing the film.

In a weirdly charming sort of way, The Big Lebowski is remarkably vulgar. The f-bomb, or some variation thereof, is used almost 300 times over the course of a two hour film. Strangely, it never feels as though the film is vulgar just for the sake of it. There are times when the vulgarity appears in nearly every line, but it seems to work with these characters. These frustrated, unlikeable characters throw the word around because that is who they are. They’re not badass cops, they’re slackers that are beyond their prime and have done nothing with their lives. All of the characters seem to have something wrong with them, but watching them one-up each other with escalating idiocy is where the true fun lies.

Overall, what makes The Big Lebowski such a pleasant and entertaining is its quirkiness: it’s unapologetically strange, yet it never feels that it is trying to hard or being weird for the sake of being weird. It’s surreal like a Coen film should be: quirky without shoving an indie vibe down our throats. The characters are endlessly quirky without feeling forced or even exaggerated. It’s just the right mixture of the realistic and the surrealistic. And it’s a total blast. The Big Lebowski is easy to find for cheap (and it’s streaming on Netflix). For a true slice of cult classic greatness, look no further than this dark, screwball comic gem.

Posted on December 2, 2011, in Hall of Greats. Bookmark the permalink. Leave a comment.

Leave a comment

Comments 0